the following primeval kings of Egypt. We arrange them in their apparent historical order.

1. Aha Men (?).

2. Narmer (or Betjumer) Sma (?).

3. Tjer (or Khent). Besh.

4. Tja Ati.

5. Den Semti.

6. Atjab Merpeba.

7. Semerkha Nekht.

8. Qâ Sen.

9. Khâsekhem (Khâsekhemui)

10. Hetepsekhemui.

11. Räneb.

12. Neneter.

13. Sekhemab Perabsen.

Two or three other names are ascribed by Prof. Petrie to the Hierakonpolite dynasty of Upper Egypt, which, as it occurs before the time of Mena and the Ist Dynasty, he calls “Dynasty 0.” Dynasty 0, however, is no dynasty, and in any case we should prefer to call the “predynastic” dynasty “Dynasty I.” The names of “Dynasty minus One,” however, remain problematical, and for the present it would seem safer to suspend judgment as to the place of the supposed royal names “Ro” and “Ka”(Men-kaf), which Prof. Petrie supposes to have been those of two of the kings of Upper Egypt who reigned before Mena. The king “Sma”(“Uniter”) is possibly identical with Aha or Narmer, more probably the latter. It is not necessary to detail the process by which Egyptologists have sought to identify these thirteen kings with the successors of Mena in the lists of kings and the Ist and IId Dynasties of Manetho. The work has been very successful, though not perhaps quite so completely accomplished as Prof. Petrie himself inclines to believe. The first identification was made by Prof. Sethe, of Gottingen, who pointed out that the names Semti and Merpeba on a vase-fragment found by M. Amélineau were in reality those of the kings Hesepti and Merbap of the lists, the Ousaphaïs and Miebis of Manetho. The perfectly certain identifications are these:—

5. Den Semti = Hesepti, Ousaphaïs, Ist Dynasty.

6. Atjab Merpeba = Merbap, Miebis, Ist Dynasty.

7. Semerkha Nekht= Shemsu or Semsem (?), Semempres, Ist Dynasty.

8. Qâ Sen = Qebh, Bienehhes, Ist Dynasty.

9. Khâsekhemui Besh = Betju-mer (?), Boethos, IId Dynasty.

10. Neneter = Bineneter, Binothris, IId Dynasty.

Six of the Abydos kings have thus been identified with names in the lists and in Manetho; that is to say, we now know the real names of six of the earliest Egyptian monarchs, whose appellations are given us under mutilated forms by the later list-makers. Prof. Petrie further identifies (4) Tja Ati with Ateth, (3) Tjer with Teta, and (1) Aha with Mena. Mena, Teta, Ateth, Ata, Hesepti, Merbap, Shemsu (?), and Qebh are the names of the 1st Dynasty as given in the lists. The equivalent of Ata Prof. Petrie finds in the name “Merneit,” which is found at Umm el-Ga’ab. But there is no proof whatever that Merneit was a king; he was much more probably a prince or other great personage of the reign of Den, who was buried with the kings. Prof. Petrie accepts the identification of the personal name of Aha as “Men,” and so makes him the only equivalent of Mena. But this reading of the name is still doubtful. Arguing that Aha must be Mena, and having all the rest of the kings of the Ist Dynasty identified with the names in the lists, Prof. Petrie is compelled to exclude Narmer from the dynasty, and to relegate him to “Dynasty 0,” before the time of Mena. It is quite possible, however, that Narmer was the successor, not the predecessor, of Mena. He was certainly either the one or the other, as the style of art in his time was exactly the same as that in the time of Aha. The “Scorpion,” too, whose name is found at Hierakonpolis, certainly dates to the same time as Narmer and Aha, for the style of his work is the same. And it may well be that he is not to be counted as a separate king, belonging to “Dynasty 0 “(or “Dynasty -I”) at all, but as identical with Narmer, just as “Sma” may also be. We thus find that the two kings who left the most developed remains at Hierakonpolis are the two whose monuments at Abydos are the oldest of all on that site. That is to say, the kings whose monuments record the conquest of the North belong to the period of transition from the old Hierakonpolite dominion of Upper Egypt to the new kingdom of all Egypt. They, in fact, represent the “Mena” or Menés of tradition. It may be that Aha bore the personal name of Men, which would thus be the original of Mena, but this is uncertain. In any case both Aha and Narmer must be assigned to the Ist Dynasty, with the result that we know of more kings belonging to the dynasty than appear in the lists.

Nor is this improbable. Manetho’s list is evidently based upon old Egyptian lists derived from the authorities upon which the king-lists of Abydos and Sakkâra were based. These old lists were made under the XIXth Dynasty, when an interest in the oldest kings seems to have been awakened, and the ruling monarchs erected temples at Abydos in their honour. This phenomenon can only have been due to a discovery of Umm el-Ga’ab and its treasures, the tombs of which were recognized as the burial-places (real or secondary) of the kings before the pyramid-builders. Seti I. and his son Ramses then worshipped the kings of Umm el-Ga’ab, with their names set before them in the order, number, and spelling in which the scribes considered they ought to be inscribed. It is highly probable that the number known at that time was not quite correct. We know that the spelling of the names was very much garbled (to take one example only, the signs for Sen were read as one sign Qebh), so that one or two kings may have been omitted or displaced. This may be the case with Narmer, or, as his name ought possibly to be read, Betjumer. His monuments show by their style that he belongs to the very beginning of the Ist Dynasty. No name in the Ist Dynasty list corresponds to his. But one of the lists gives for the first king of the IId Dynasty (the successor of “Qebh” = Sen) a name which may also be read Betjumer, spelt syllabically this time, not ideographically. On this account Prof. Naville wishes to regard the Hierakonpolite monuments of Narmer as belonging to the IId Dynasty, but, as we have seen, they are among the most archaic known, and certainly must belong to the beginning of the Ist Dynasty. It is therefore probable that Khasekhemui Besh and Narmer (Betjumer?) were confused by this list-maker, and the name Betjumer was given to the first king of the IId Dynasty, who was probably in reality Khasekhemui. The resemblance of Betju to Besh may have contributed to this confusion.

So Narmer (or Betjumer) found his way out of his proper place at the beginning of the 1st Dynasty. Whether Aha was also called “Men” or not, it seems evident that he and Narmer were jointly the originals of the legendary Mena. Narmer, who possibly also bore the name of Sma, “the Uniter,” conquered the North. Aha, “the Fighter,” also ruled both South and North at the same period. Khasekhemui, too, conquered the North, but the style of his monuments shows such an advance upon that of the days of Aha and Narmer that it seems best to make him the successor of Sen (or “Qebh “), and, explaining the transference of the name Betjumer to the beginning of the IId Dynasty as due to a confusion with Khasekhemui’s personal name Besh, to make Khasekhemui the founder of the IId Dynasty. The beginning of a new dynasty may well have been marked by a reassertion of the new royal power over Lower Egypt, which may have lapsed somewhat under the rule of the later kings of the Ist Dynasty.

Semti is certainly the “Hesepti” of the lists, and Tja Ati is probably “Ateth.” “Ata” is thus unidentified. Prof. Petrie makes him = Merneit, but, as has already been said, there is no proof that the tomb of Merneit is that of a king. “Teta” may be Tjer or Khent, but of this there is no proof. It is most probable that the names “Teta,” “Ateth,” and “Ata” are all founded on Ati, the personal name of Tja. The king Tjer is then not represented in the lists, and “Mena” is a compound of the two oldest Abydos kings, Narmer (Betjumer) Sma (?) and Aha Men (?).

These are the bare historical results that have been attained with regard to the names, identity, and order of the kings. The smaller memorials that have been found with them, especially the ivory plaques, have told us of events that took place during their reigns; but, with the exception of the constantly recurring references to the conquest of the North, there is little that can be considered of historical interest or importance. We will take one as an example. This is the tablet No. 32,650 of the British Museum, illustrated by Prof. Petrie, Royal Tombs i (Egypt Exploration Fund), pi. xi, 14, xv, 16. This is the record of a single year, the first in the reign of Semti, King of Upper and Lower Egypt. On it we see a picture of a king performing a religious dance before the god Osiris, who is seated in a shrine placed on a dais. This religious dance was performed by all the kings in later times. Below we find hieroglyphic (ideographic) records of a river expedition to fight the Northerners and of the capture of a fortified town called An. The capture of the town is indicated by a broken line of fortification, half-encircling the name, and the hoe with which the emblematic hawks on the slate reliefs already described are armed; this signifies the opening and breaking down of the wall.

On the other half of the tablet we find the viceroy of Lower Egypt, Hemaka, mentioned; also “the Hawk (i. e. the king) seizes the seat of the Libyans,” and some unintelligible record of a jeweller of the palace and a king’s carpenter. On a similar tablet (of Sen) we find the words “the king’s carpenter made this record.” All these little tablets are then the records of single years of a king’s life, and others like them, preserved no doubt in royal archives, formed the base of regular annals, which were occasionally carved upon stone. We have an example of one of these in the “Stele of Palermo,” a fragment of black granite, inscribed with the annals of the kings up to the time of the Vth Dynasty, when the monument itself was made. It is a matter for intense regret that the greater portion of this priceless historical monument has disappeared, leaving us but a piece out of the centre, with part of the records of only six kings before Snefru. Of these six the name of only one, Neneter, of the lid Dynasty, whose name is also found at Abydos, is mentioned. The only important historical event of Neneter’s reign seems to have occurred in his thirteenth year, when the towns or palaces of Ha (“North”) and Shem-Râ (“The Sun proceeds”) were founded. Nothing but the institution and celebration of religious festivals is recorded in the sixteen yearly entries preserved to us out of a reign of thirty-five years. The annual height of the Nile is given, and the occasions of numbering the people are recorded (every second year): nothing else. Manetho tells us that in the reign of Binothris, who is Neneter, it was decreed that women could hold royal honours and privileges. This first concession of women’s rights is not mentioned on the strictly official “Palermo Stele.”

More regrettable than aught else is the absence from the “Palermo Stele” of that part of the original monument which gave the annals of the earliest kings. At any rate, in the lines of annals which still exist above that which contains the chronicle of the reign of Neneter no entry can be definitely identified as belonging to the reigns of Aha or Narmer. In a line below there is a mention of the “birth of Khâsekhemui,” apparently a festival in honour of the birth of that king celebrated in the same way as the reputed birthday of a god. This shows the great honour in which Khâsekhemui was held, and perhaps it was he who really finally settled the question of the unification of North and South and consolidated the work of the earlier kings.

As far as we can tell, then, Aha and Narmer were the first conquerors of the North, the unifiers of the kingdom, and the originals of the legendary Mena. In their time the kingdom’s centre of gravity was still in the South, and Narmer (who is probably identical with “the Scorpion”) dedicated the memorials of his deeds in the temple of Hierakonpolis. It may be that the legend of the founding of Memphis in the time of “Menés” is nearly correct (as we shall see, historically, the foundation may have been due to Merpeba), but we have the authority of Manetho for the fact that the first two dynasties were “Thinite” (that is, Upper Egyptian), and that Memphis did not become the capital till the time of the Hid Dynasty. With this statement the evidence of the monuments fully agrees. The earliest royal tombs in the pyramid-field of Memphis date from the time of the Hid Dynasty, so that it is evident that the kings had then taken up their abode in the Northern capital. We find that soon after the time of Khâsekhemui the king Perabsen was especially connected with Lower Egypt. His personal name is unknown to us (though he may be the “Uatjnes” of the lists), but we do know that he had two banner-names, Sekhem-ab and Perabsen. The first is his hawk or Horus-name, the second his Set-name; that is to say, while he bore the first name as King of Upper Egypt under the special patronage of Horus, the hawk-god of the Upper Country, he bore the second as King of Lower Egypt, under the patronage of Set, the deity of the Delta, whose fetish animal appears above this name instead of the hawk. This shows how definitely Perabsen wished to appear as legitimate King of Lower as well as Upper Egypt. In later times the Theban kings of the XIIth Dynasty, when they devoted themselves to winning the allegiance of the Northerners by living near Memphis rather than at Thebes, seem to have been imitating the successors of Khâsekhemui.

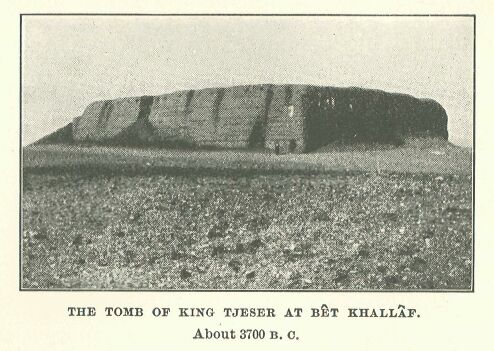

Moreover, we now find various evidences of increasing connection with the North. A princess named Ne-maat-hap, who seems to have been the mother of Sa-nekht, the first king of the Hid Dynasty, bears the name of the sacred Apis of Memphis, her name signifying “Possessing the right of Apis.” According to Manetho, the kings of the Hid Dynasty are the first Memphites, and this seems to be quite correct. With Ne-maat-hap the royal right seems to have been transferred to a Memphite house. But the Memphites still had associations with Upper Egypt: two of them, Tjeser Khet-neter and Sa-nekht, were buried near Abydos, in the desert at Bêt Khallâf, where their tombs were discovered and excavated by Mr. Garstang in 1900. The tomb of Tjeser is a great brick-built mastaba, forty feet high and measuring 300 feet by 150 feet. The actual tomb-chambers are excavated in the rock, twenty feet below the ground-level and sixty feet below the top of the mastaba. They had been violated in ancient times, but a number of clay jar-sealings, alabaster vases, and bowls belonging to the tomb furniture were found by the discoverer. Sa-nekht’s tomb is similar. In it was found the preserved skeleton of its owner, who was a giant seven feet high.

Tjeser had two tombs, one, the above-mentioned, near Abydos, the other at Sakkâra, in the Memphite pyramid-field. This is the famous Step-Pyramid. Since Sa-nekht seems really to have been buried at Bêt Khal-laf, probably Tjeser was, too, and the Step-Pyramid may have been his secondary or sham tomb, erected in the necropolis of Memphis as a compliment to Seker, the Northern god of the dead, just as Aha had his secondary tomb at Abydos in compliment to Khentamenti. Sne-feru, also, the last king of the Hid Dynasty, seems to have had two tombs. One of these was the great Pyramid of Mêdûm, which was explored by Prof. Petrie in 1891, the other was at Dashûr. Near by was the interesting necropolis already mentioned, in which was discovered evidence of the continuance of the cramped position of burial and of the absence of mummification among a certain section of the population even as late as the time of the IVth Dynasty. This has been taken to imply that the fusion of the primitive Neolithic and invading sub-Semitic races had not been effected at that time.

With the IVth Dynasty the connection of the royal house with the South seems to have finally ceased. The governmental centre of gravity was finally transferred to Memphis, and the kings were thenceforth for several centuries buried in the great pyramids which still stand in serried order along the western desert border of Egypt, from the Delta to the province of the Fayyum. With the latest discoveries in this Memphite pyramid-field we shall deal in the next chapter.

The transference of the royal power to Memphis under the Hid Dynasty naturally led to a great increase of Egyptian activity in the Northern lands. We read in Manetho of a great Libyan war in the reign of Neche-rophes, and both Sa-nekht and Tjeser seem to have finally established Egyptian authority in the Sinaitic peninsula, where their rock-inscriptions have been found.

In 1904 Prof. Petrie was despatched to Sinai by the Egypt Exploration Fund, in order finally to record the inscriptions of the early kings in the Wadi Maghara, which had been lately very much damaged by the operations of the turquoise-miners. It seems almost incredible that ignorance and vandalism should still be so rampant in the twentieth century that the most important historical monuments are not safe from desecration in order to obtain a few turquoises, but it is so. Prof. Petrie’s expedition did not start a day too soon, and at the suggestion of Sir William Garstin, the adviser to the Ministry of the Interior, the majority of the inscriptions have been removed to the Cairo Museum for safety and preservation. Among the new inscriptions discovered is one of Sa-nekht, which is now in the British Museum. Tjeser and Sa-nekht were not the first Egyptian kings to visit Sinai. Already, in the days of the 1st Dynasty, Semerkha had entered that land and inscribed his name upon the rocks. But the regular annexation, so to speak, of Sinai to Egypt took place under the Memphites of the Hid Dynasty.

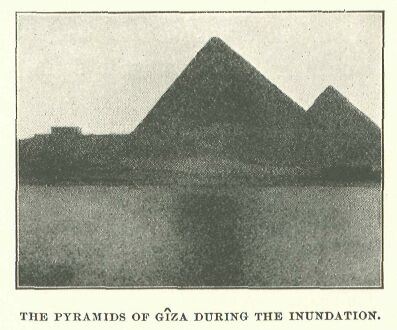

With the Hid Dynasty we have reached the age of the pyramid-builders. The most typical pyramids are those of the three great kings of the IVth Dynasty, Khufu, Khafra, and Menkaura, at Giza near Cairo. But, as we have seen, the last king of the Hid Dynasty, Snefru, also had one pyramid, if not two; and the most ancient of these buildings known to us, the Step-Pyramid of Sakkâra, was erected by Tjeser at the beginning of that dynasty. The evolution of the royal tombs from the time of the 1st Dynasty to that of the IVth is very interesting to trace. At the period of transition from the predynastic to the dynastic age we have the great mastaba of Aha at Nakâda, and the simplest chamber-tombs at Abydos. All these were of brick; no stone was used in their construction. Then we find the chamber-tomb of Den Semti at Abydos with a granite floor, the walls being still of brick. Above each of the Abydos tombs was probably a low mound, and in front a small chapel, from which a flight of steps descended into the simple chamber. On one of the little plaques already mentioned, which were found in these tombs, we have an archaic inscription, entirely written in ideographs, which seems to read, “The Big-Heads (i. e. the chiefs) come to the tomb.” The ideograph for “tomb” seems to be a rude picture of the funerary chapel, but from it we can derive little information as to its construction. Towards the end of the Ist Dynasty, and during the lid, the royal tombs became much more complicated, being surrounded with numerous chambers for the dead slaves, etc. Khâsekhemui’s tomb has thirty-three such chambers, and there is one large chamber of stone. We know of no other instance of the use of stone work for building at this period except in the royal tombs. No doubt the mason’s art was still so difficult that it was reserved for royal use only.

Under the Hid Dynasty we find the last brick mastabas built for royalty, at Bêt Khallâf, and the first pyramids, in the Memphite necropolis. In the mastaba of Tjeser at Bêt Khallâf stone was used for the great portcullises which were intended to bar the way to possible plunderers through the passages of the tomb. The Step-Pyramid at Sakkâra is, so to speak, a series of mastabas of stone, imposed one above the other; it never had the continuous casing of stone which is the mark of a true pyramid. The pyramid of Snefru at Mêdûm is more developed. It also originated in a mastaba, enlarged, and with another mastaba-like erection on the top of it; but it was given a continuous sloping casing of fine limestone from bottom to top, and so is a true pyramid. A discussion of recent theories as to the building of the later pyramids of the IVth Dynasty will be found in the next chapter.

In the time of the Ist Dynasty the royal tomb was known by the name of “Protection-around-the-Hawk, i.e. the king”(Sa-ha-heru); but under the Hid and IVth Dynasties regular names, such as “the Firm,” “the Glorious,” “the Appearing,” etc., were given to each pyramid.

It may seem remarkable that all this new knowledge of ancient Egypt is derived from tombs and has to do with the resting-places of the kings when dead, rather than with their palaces or temples when living. Of temples at this early period we have no trace. The oldest temple in Egypt is perhaps the little chapel in front of the pyramid of Snefru at Mêdûm. We first hear of temples to the gods under the IVth Dynasty, but of the actual buildings of that period we have recovered nothing but one or two inscribed blocks of stone. Prof. Petrie has traced out the plan of the oldest temple of Osiris at Abydos, which may be of the time of Khufu, from scanty evidences which give us but little information. It is certain, however, that this temple, which is clearly one of the oldest in Egypt, goes back at least to his time. Its site is the mound called Kom es-Sultan, “The Mound of the King,” close to the village of el-Kherba, and on the borders of the cultivation northeast of the royal tombs at Umm el-Oa’ab.

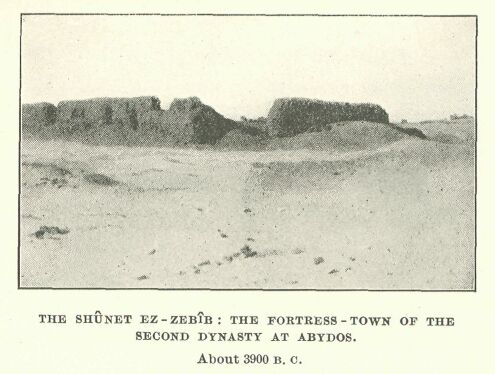

Of royal palaces we have more definite information. North of the Kom es-Sultan are two great fortress-enclosures of brick: the one is known as Sûnet es-Zebîb, “the Storehouse of Dried Orapes;” the other is occupied by the Coptic monastery of Dêr Anba Musâs. Both are certainly fortress-palaces of the earliest period of the Egyptian monarchy. We know from the small record-plaques of this period that the kings were constantly founding or repairing places of this kind, which were always great rectangular enclosures with crenelated brick walls like those of early Babylonian buildings.

We have seen that the Northern Egyptian possessed similar fortress-cities which were captured by Narmer. These were the seats of the royal residence in various parts of the country. Behind their walls was the king’s house, and no doubt also a town of nobles and retainers, while the peasants lived on the arable land without.

It will have been seen from the foregoing description of what far-reaching importance the discoveries at Abydos have been. A new chapter of the history of the human race has been opened, which contains information previously undreamt of, information which Egyptologists had never dared to hope would be recovered. The sand of Egypt indeed conceals inexhaustible treasures, and no one knows what the morrow’s work may bring forth.

Ex Africa semper aliquid novi!

CHAPTER III—MEMPHIS AND THE PYRAMIDS

Memphis, the “beautiful abode,” the “City of the White Wall,” is said to have been founded by the legendary Menés, who in order to build it diverted the stream of the Nile by means of a great dyke constructed near the modern village of Koshêsh, south of the village of Mitrahêna, which marks the central point of the ancient metropolis of Northern Egypt. It may be that the city was founded by Aha or Narmer, the historical originals of Mena or Menés; but we have another theory with regard to its foundation, that it was originally built by King Merpeba Atjab, whose tomb was also discovered at Abydos near those of Aha and Narmer. Merpeba is the oldest king whose name is absolutely identified with one occurring in the XIXth Dynasty king-lists and in Manetho. He is certainly the “Merbap” or “Merbepa” (“Merbapen”) of the lists and the Miebis of Manetho. In both the lists and in Manetho he stands fifth in order from Mena, and he was therefore the sixth king of the Ist Dynasty. The lists, Manetho, and the small monuments in his own tomb agree in making him the immediate successor of Semti Den (Ousaphaïs), and from the style of these latter it is evident that he comes after Tja, Tjer, Narmer, and Aha. That is to say, the contemporary evidence makes him the fifth king from Aha, the first original of “Menés.”Now after the piety of Seti I had led him to erect a great temple at Abydos in memory of the ancient kings, whose sepulchres had probably been brought to light shortly before, and to compile and set up in the temple a list of his predecessors, a certain pious snobbery or snobbish piety impelled a worthy named Tunure, who lived at Memphis, to put up in his own tomb at Sakkâra a tablet of kings like the royal one at Abydos. If Osiris-Khentamenti at Abydos had his tablet of kings, so should Osiris-Seker at Sakkâra. But Tunure does not begin his list with Mena; his initial king is Merpeba. For him Merpeba was the first monarch to be commemorated at Sakkâra. Does not this look very much as if the strictly historical Merpeba, not the rather legendary and confused Mena, was regarded as the first Memphite king? It may well be that it was in the reign of Merpeba, not in that of Aha or Narmer, that Memphis was founded.

The XIXth Dynasty lists of course say nothing about Mena or Merpeba having founded Memphis; they only give the names of the kings, nothing more. The earliest authority for the ascription of Memphis to “Menés”, is Herodotus, who was followed in this ascription, as in many other matters, by Manetho; but it must be remembered that Manetho was writing for the edification of a Greek king (Ptolemy Philadelphus) and his Greek court at Alexandria, and had therefore to evince a respect for the great Greek classic which he may not always have really felt. Herodotus is not, of course, accused of any wilful misstatement in this or in any other matter in which his accuracy is suspected. He merely wrote down what he was told by the Egyptians themselves, and Merpeba was sufficiently near in time to Aha to be easily confounded with him by the scribes of the Persian period, who no doubt ascribed everything to “Mena” that was done by the kings of the Ist and IId Dynasties. Therefore it may be considered quite probable that the “Menés” who founded Memphis was Merpeba, the fifth or sixth king of the Ist Dynasty, whom Tunure, a thousand years before the time of Herodotus and his informants, placed at the head of the Memphite “List of Sakkâra.”

The reconquest of the North by Khâsekhemui doubtless led to a further strengthening of Memphis; and it is quite possible that the deeds of this king also contributed to make up the sum total of those ascribed to the Herodotean and Manethonian Menés.

It may be that a town of the Northerners existed here before the time of the Southern Conquest, for Phtah, the local god of Memphis, has a very marked character of his own, quite different from that of Khen-tamenti, the Osiris of Abydos. He is always represented as a little bow-legged hydrocephalous dwarf very like the Phoenician Kabeiroi. It may be that here is another connection between the Northern Egyptians and the Semites. The name “Phtah,” the “Opener,” is definitely Semitic. We may then regard the dwarf Phtah as originally a non-Egyptian god of the Northerners, probably Semitic in origin, and his town also as antedating the conquest. But it evidently was to the Southerners that Memphis owed its importance and its eventual promotion to the position of capital of the united kingdom. Then the dwarf Phtah saw himself rivalled by another Phtah of Southern Egyptian origin, who had been installed at Memphis by the Southerners. This Phtah was a sort of modified edition of Osiris, in mummy-form and holding crook and whip, but with a refined edition of the Kabeiric head of the indigenous Phtah. The actual god of “the White Wall” was undoubtedly confused vith the dead god of the necropolis, whose name was Seker or Sekri (Sokari), “the Coffined.” The original form of this deity was a mummied hawk upon a coffin, and it is very probable that he was imported from the South, like the second Phtah, at the time of the conquest, when the great Northern necropolis began to grow up as a duplicate of that at Abydos. Later on we find Seker confused with the ancient dwarf-god, and it is the latter who was afterwards chiefly revered as Phtah-Socharis-Osiris, the protector of the necropolis, the mummied Phtah being the generally recognized ruler of the City of the White Wall.

It is from the name of Seker that the modern Sak-kâra takes its title. Sakkâra marks the central point of the great Memphite necropolis, as it is the nearest point of the western desert to Memphis. Northwards the necropolis extended to Griza and Abu Roâsh, southwards, to Daslmr; even the nécropoles of Lisht and Mêdûm may be regarded as appanages of Sakkâra. At Sakkâra itself Tjeser of the IIId Dynasty had a pyramid, which, as we have seen, was probably not his real tomb (which was the great mastaba at Bêt Khallâf), but a secondary or sham tomb corresponding to the “tombs” of the earliest kings at Umm el-Ga’ab in the necropolis of Abydos. Many later kings, however, especially of the Vith Dynasty, were actually buried at Sakkâra. Their tombs have all been thoroughly described by their discoverer, Prof. Maspero, in his history. The last king of the Hid Dynasty, Snefru, was buried away down south at Mêdûm, in splendid isolation, but he may also have had a second pyramid at Sakkâra or Abu Roash.

The kings of the IVth Dynasty were the greatest of the pyramid builders, and to them belong the huge edifices of Griza. The Vth Dynasty favoured Abusîr, between Cîza and Sakkâra; the Vith, as we have said, preferred Sakkâra itself. With them the end of the Old Kingdom and of Memphite dominion was reached; the sceptre fell from the hands of the Memphite kings and was taken up by the princes of Herakleopolis (Ahnasyet el-Medina, near Béni Suêf, south of the Eayyûm) and Thebes. Where the Herakleopolite kings were buried we do not know; probably somewhere in the local necropolis of the Gebel es-Sedment, between Ahnasya and the Fayyûm. The first Thebans (the XIth Dynasty) were certainly buried at Thebes, but when the Herakleopolites had finally disappeared, and all Egypt was again united under one strong sceptre, the Theban kings seem to have been drawn northwards. They removed to the seat of the dominion of those whom they had supplanted, and they settled in the neighbourhood of Herakleopolis, near the fertile province of the Fayyûm, and between it and Memphis. Here, in the royal fortress-palace of Itht-taui, “Controlling the Two Lands,” the kings of the XIIth Dynasty lived, and they were buried in the nécropoles of Dashûr, Lisht, and Illahun (Hawara), in pyramids like those of the old Memphite kings. These facts, of the situation of Itht-taui, of their burial in the southern an ex of the old necropolis of Memphis, and of the fori of their tombs (the true Upper Egyptian and Thebian form was a rock-cut gallery and chamber driven deep into the hill), show how solicitous were the Amenemhats and Senusrets of the suffrages of Lower Egypt, how anxious they were to conciliate the ancient royal pride of Memphis.

Where the kings of the XIIIth Dynasty and the Hyksos or “Shepherds” were buried, we do not know. The kings of the restored Theban empire were all interred at Thebes. There are, in fact, no known royal sepulchres between the Fayyûm and Abydos. The great kings were mostly buried in the neighbourhood of Memphis, Abydos, and Thebes. The sepulchres of the “Middle Empire”—the XIth to XIIIth Dynasties—in the neighbourhood of the Fayyûm may fairly be grouped with those of the same period at Dashûr, which belongs to the necropolis of Memphis, since it is only a mile or two south of Sakkâra.

It is chiefly with regard to the sepulchres of the kings that the most momentous discoveries of recent years have been made at Thebes, and at Sakkâra, Abusîr, Dashûr, and Lisht, as at Abydos. For this reason we deal in succession with the finds in the nécropoles of Abydos, Memphis, and Thebes respectively. And with the sepulchres of the “Old Kingdom,” in the Memphite necropolis proper, we have naturally grouped those of the “Middle Kingdom” at Dashûr, Lisht, Illahun, and Hawara.

Some of these modern discoveries have been commented on and illustrated by Prof. Maspero in his great history. But the discoveries that have been made since this publication have been very important,—those at Abusîr, indeed, of first-rate importance, though not so momentous as those of the tombs of the Ist and IId Dynasties at Abydos, already described. At Abu Roash and at Gîza, at the northern end of the Memphite necropolis, several expeditions have had considerable success, notably those of the American Dr. Reisner, assisted by Mr. Mace, who excavated the royal tombs at Umm el-Ga’ab for Prof. Petrie, those of the German Drs. Steindorff and Borchardt,—the latter working for the Beutsch-Orient Gesellschaft,—and those of other American excavators. Until the full publication of the results of these excavations appears, very little can be said about them. Many mastaba-tombs have, it is understood, been found, with interesting remains. Nothing of great historical importance seems to have been discovered, however. It is otherwise when we come to the discoveries of Messrs. Borchardt and Schâfer at Abusîr, south of Gîza and north of Sakkâra. At this place results of first-rate historical importance have been attained.

The main group of pyramids at Abusir consists of the tombs of the kings Sahurà, Neferarikarâ, and Ne-user-Râ, of the Vth Dynasty. The pyramids themselves are smaller than those of Gîza, but larger than those of Sakkâra. In general appearance and effect they resemble those of Gîza, but they are not so imposing, as the desert here is low. Those of Gîza, Sakkâra, and Dashûr owe much of their impressiveness to the fact that they are placed at some height above the cultivated land. The excavation and planning of these pyramids were carried out by Messrs. Borchardt and Schâfer at the expense of Baron von Bissing, the well-known Egyptologist of Munich, and of the Deutsch-Orient Gesell-schaft of Berlin. The antiquities found have been divided between the museums of Berlin and Cairo.

One of the most noteworthy discoveries was that of the funerary temple of Ne-user-Râ, which stood at the base of his pyramid. The plan is interesting, and the granite lotus-bud columns found are the most ancient yet discovered in Egypt. Much of the paving and the wainscoting of the walls was of fine black marble, beautifully polished. An interesting find was a basin and drain with lion’s-head mouth, to carry away the blood of the sacrifices. Some sculptures in relief were discovered, including a gigantic representation of the king and the goddess Isis, which shows that in the early days of the Vth Dynasty the king and the gods were already depicted in exactly the same costume as they wore in the days of the Ramses and the Ptolemies. The hieratic art of Egypt had, in fact, now taken on itself the final outward appearance which it retained to the very end. There is no more of the archaism and absence of conventionality, which marks the art of the earliest dynasties.

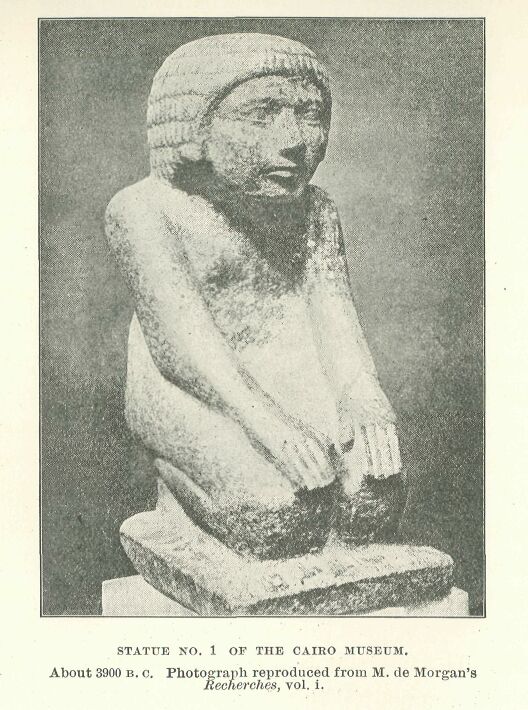

We can trace by successive steps the swift development of Egyptian art from the rude archaism of the Ist Dynasty to its final consummation under the Vth, when the conventions became fixed. In the time of Khäsekhemui, at the beginning of the IId Dynasty, the archaic character of the art has already begun to wear off. Under the same dynasty we still have styles of unconventional naïveté, such as the famous Statue “No. 1” of the Cairo Museum, bearing the names of Kings Hetepahaui, Neb-râ, and Neneter. But with the IVth Dynasty we no longer look for unconventionality. Prof. Petrie discovered at Abydos a small ivory statuette of Khufu or Cheops, the builder of the Great Pyramid of Gîza. The portrait is a good one and carefully executed. It was not till the time of the XVIIIth Dynasty, indeed, that the Egyptians ceased to portray their kings as they really were, and gave them a purely conventional type of face. This convention, against which the heretical King Amenhetep IV (Akhunaten) rebelled, in order to have himself portrayed in all his real ungainliness and ugliness, did not exist till long after the time of the IVth and Vth Dynasties.

But the general conventions of dress and deportment were finally fixed under the Vth Dynasty. After this time we no longer have such absolutely faithful and original presentments as the other little ivory statuette found by Prof. Petrie at Abydos (now in the British Museum), which shows us an aged monarch of the Ist Dynasty. It is obvious that the features are absolutely true to life, and the figure wears an unconventionally party-coloured and bordered robe of a kind which kings of a later day may have worn in actual life, but which they would assuredly never be depicted as wearing by the artists of their day. To the end of Egyptian history, the kings, even the Roman emperors, were represented on the monuments clothed in the official costume of their ancestors of the IVth and Vth Dynasties, in the same manner as we see Khufu wearing his robe in the little figure from Abydos, and Ne-user-Rà on the great relief from Abusîr. There are one or two exceptions, such as the representations of the original genius Akhunaten at Tell el-Amarna and the beautiful statue of Ramses II at Turin, in which we see these kings wearing the real costume of their time, but such exceptions are very rare.

The art of Abusîr is therefore of great interest, since it marks the end of the development of the priestly art. Secular art might develop as it liked, though the crystallizing influence of the ecclesiastical canon is always evident here also. But henceforward it was an impiety, which only an Akhunaten could commit, to depict a king or a god on the walls of a temple otherwise (except so far as, the portrait was concerned) than as he had been depicted in the time of the Vth Dynasty.

Other buildings have been excavated by the Germans at Abusîr, notably the usual town of mastaba-tombs belonging to the chief dignitaries of the reign, which is always found at the foot of a royal pyramid of this period. Another building of the highest interest, belonging to the same age, was also excavated, and its true character was determined. This is a building at a place called er-Rîgha or Abû Ghuraib, “Father of Crows,” between Abusîr and Gîza. It was formerly supposed to be a pyramid, but the German excavations have shown that it is really a temple of the Sun-god Râ of Heliopolis, specially venerated by the kings of the Vth Dynasty, who were of Heliopolitan origin. The great pyramid-builders of the IVth Dynasty seem to have been the last true Memphites. At the end of the reign of Shepseskaf, the last monarch of the dynasty, the sceptre passed to a Heliopolitan family. The following VIth Dynasty may again have been Memphite, but this is uncertain. The capital continued to be Memphis, and from the beginning of the Hid Dynasty to the end of the Old Kingdom and the rise of Herakle-opolis and Thebes, Memphis remained the chief city of Egypt.

The Heliopolitans were naturally the servants of the Sun-god above all other gods, and they were the first to call themselves “Sons of the Sun,” a title retained by the Pharaohs throughout all subsequent history. It was Ne-user-Râ who built the Sun-temple of Abu Ghuraib, on the edge of the desert, north of his pyramid and those of his two immediate predecessors at Abusir. As now laid bare by the excavations of 1900, it is seen to consist of an artificial mound, with a great court in front to the eastward. On the mound was erected a truncated obelisk, the stone emblem of the Sun-god. The worshippers in the court below looked towards the Sun’s stone erected upon its mound in the west, the quarter of the sun’s setting; for the Sun-god of Heliopolis was primarily the setting sun, Tum-Râ, not Râ Harmachis, the rising sun, whose emblem is the Great Sphinx at Gîza, which looks towards the east. The sacred emblem of the Heliopolitan Sun-god reminds us forcibly of the Semitic bethels or baetyli, the sacred stones of Palestine, and may give yet another hint of the Semitic origin of the Heliopolitan cult. In the court of the temple is a huge circular altar of fine alabaster, several feet across, on which slain oxen were offered to the Sun, and behind this, at the eastern end of the court, are six great basins of the same stone, over which the beasts were slain, with drains running out of them by which their blood was carried away. This temple is a most interesting monument of the civilization of the “Old Kingdom” at the time of the Vth Dynasty.

At Sakkâra itself, which lies a short distance south of Abusir, no new royal tombs have, as has been said, been discovered of late years. But a great deal of work has been done among the private mastaba-tombs by the officers of the Service des Antiquités, which reserves to itself the right of excavation here and at Dashûr. The mastaba of the sage and writer Kagernna (or rather Gemnika, “I-have-found-a-ghost,” which sounds very like an American Indian appellation) is very fine. “I-have-found-a-ghost” lived in the reign of the king Tatkarâ Assa, the “Tancheres” of Manetho, and he wrote maxims like his great contemporary Phtahhetep (“Offered to Phtah”), who was also buried at Sakkâra. The officials of the Service des Antiquités who cleaned the tomb unluckily misread his name Ka-bi-n (an impossible form which could only mean, literally translated, “Ghost-soul-of” or “Ghost-soul-to-me”), and they have placed it in this form over the entrance to his tomb. This mastaba, like those, already known, of Mereruka (sometimes misnamed “Mera”) and the famous Ti, both also at Sakkâra, contains a large number of chambers, ornamented with reliefs. In the vicinity M. Grébaut, then Director of the Service of Antiquities, discovered a very interesting Street of Tombs, a regular Via Sacra, with rows of tombs of the dignitaries of the VIth Dynasty on either side of it. They are generally very much like one another; the workmanship of the reliefs is fine, and the portrait of the owner of the tomb is always in evidence.

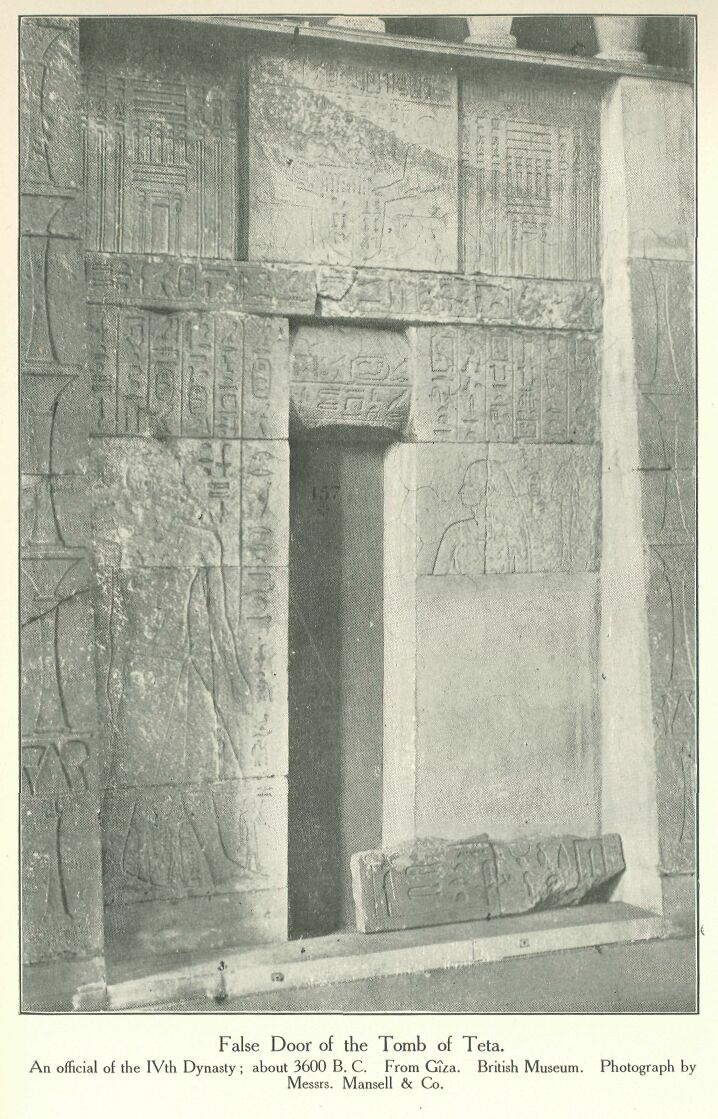

Several of the smaller mastabas have lately been disposed of to the various museums, as they are liable to damage if they remain where they stand; moreover, they are not of great value to the Museum of Cairo, but are of considerable value to various museums which do not already possess complete specimens of this class of tombs. A fine one, belonging to the chief Uerarina, is now exhibited in the Assyrian Basement of the British Museum; another is in the Museum of Leyden; a third at Berlin, and so on. Most of these are simple tombs of one chamber. In the centre of the rear wall we always see the stele or gravestone proper, built into the fabric of the tomb. Before this stood the low table of offerings with a bowl for oblations, and on either side a tall incense-altar. From the altar the divine smoke (senetr) arose when the hen-ka, or priest of the ghost (literally, “Ghost’s Servant”), performed his duty of venerating the spirits of the deceased, while the Kher-heb, or cantor, enveloped in the mystic folds of the leopard-skin and with bronze incense-burner in hand, sang the holy litanies and spells which should propitiate the ghost and enable him to win his way to ultimate perfection in the next world.

The stele is always in the form of a door with pyloni-form cornice. On either side is a figure of the deceased, and at the sides are carved prayers to Anubis, and at a later date to Osiris, who are implored to give the funerary meats and “everything good and pure on which the god there (as the dead man in the tomb has been constituted) lives;” often we find that the biography and list of honorary titles and dignities of the deceased have been added.

Sakkâra was used as a place of burial in the latest as well as in the earliest time. The Egyptians of the XXVIth Dynasty, wearied of the long decadence and devastating wars which had followed the glorious epoch of the conquering Pharaohs of the XVIIIth and XIXth Dynasties, turned for a new and refreshing inspiration to the works of the most ancient kings, when Egypt was a simple self-contained country, holding no intercourse with outside lands, bearing no outside burdens for the sake of pomp and glory, and knowing nothing of the decay and decadence which follows in the train of earthly power and grandeur. They deliberately turned their backs on the worn-out and discredited imperial trappings of the Thothmes and Ramses, and they took the supposed primitive simplicity of the Snefrus, the Khufus, and the Ne-user-Râs for a model and ensampler to their lives. It was an age of conscious and intended archaism, and in pursuit of the archaistic ideal the Mem-phites of the Saïte age had themselves buried in the ancient necropolis of Sakkâra, side by side with their ancestors of the time of the Vth and VIth Dynasties. Several of these tombs have lately been discovered and opened, and fitted with modern improvements. One or two of them, of the Persian period, have wells (leading to the sepulchral chamber) of enormous depth, down which the modern tourist is enabled to descend by a spiral iron staircase. The Serapeum itself is lit with electricity, and in the Tombs of the Kings at Thebes nothing disturbs the silence but the steady thumping pulsation of the dynamo-engine which lights the ancient sepulchres of the Pharaohs. Thus do modern ideas and inventions help us to see and so to understand better the works of ancient Egypt. But it is perhaps a little too much like the Yankee at the Court of King Arthur. The interiors of the later tombs are often decorated with reliefs which imitate those of the early period, but with a kind of delicate grace which at once marks them for what they are, so that it is impossible to confound them with the genuine ancient originals from which they were adapted.

Riding from Sakkâra southwards to Dashûr, we pass on the way the gigantic stone mastaba known as the Mastabat el-Fara’ûn, “Pharaoh’s Bench.” This was considered to be the tomb of the Vth Dynasty king, Unas, until his pyramid was found by Prof. Maspero at Sakkâra. From its form it might be thought to belong to a monarch of the Hid Dynasty, but the great size of the stone blocks of which it is built seems to point rather to the XIIth. All attempts to penetrate its secret by actual excavation have been unavailing.

Further south across the desert we see from the Mastabat el-Fara’ûn four distinct pyramids, symmetrically arranged in two lines, two in each line. The two to the right are great stone erections of the usual type, like those of Gîza and Abusîr, and the southernmost of them has a peculiar broken-backed appearance, due to the alteration of the angle of inclination of its sides during construction. Further, it is covered almost to the ground by the original casing of polished white limestone blocks, so that it gives a very good idea of the original appearance of the other pyramids, which have lost their casing. These two pyramids very probably belong to kings of the Hid Dynasty, as does the Step-Pyramid of Sakkâra. They strongly resemble the Gîza type, and the northernmost of the two looks very like an understudy of the Great Pyramid. It seems to mark the step in the development of the royal pyramid which was immediately followed by the Great Pyramid. But no excavations have yet proved the accuracy of this view. Both pyramids have been entered, but nothing has been found in them. It is very probable that one of them is the second pyramid of Snefru.

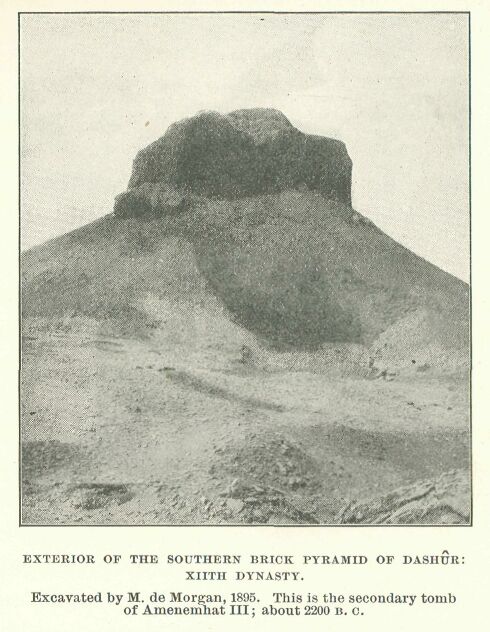

The other two pyramids, those nearest the cultivation, are of very different appearance. They are half-ruined, they are black in colour, and their whole effect is quite different from that of the stone pyramids. For they are built of brick, not of stone. They are pyramids, it is true, but of a different material and of a different date from those which we have been describing. They are built above the sepulchres of kings of the XIIth Dynasty, the Theban house which transferred its residence northwards to the neighbourhood of the ancient Northern capital. We have, in fact, reached the end of the Old Kingdom at Sakkâra; at Dashûr begin the sepulchres of the Middle Kingdom. Pyramids are still built, but they are not always of stone; brick is used, usually with stone in the interior. The general effect of these brick pyramids, when new, must have been indistinguishable from that of the stone ones, and even now, when it has become half-ruined, such a great brick pyramid as that of Usertsen (Senusret) III at Dashûr is not without impressiveness. After all, there is no reason why a brick building should be less admirable than a stone one. And in its own way the construction of such colossal masses of bricks as the two eastern pyramids of Dashûr must have been as arduous, even as difficult, as that of building a moderate-sized stone pyramid. The photograph of the brick pyramids of Dashûr on this page shows well the great size of these masses of brickwork, which are as impressive as any of the great brick structures of Babylonia and Assyria.

XIITH DYNASTY. Excavated by M. de Morgan, 1895. This is the

secondary tomb of Amenemhat III; about 2200 B.C.

The XIIth Dynasty use of brick for the royal tombs was a return to the

custom of earlier days, for from the time of Aha to that Tjeser, from the

1st Dynasty to the Hid, brick had been used for the building of the royal

mastaba-tombs, out of which the pyramids had developed.

At this point, where we take leave of the great pyramids of the Old Kingdom, we may notice the latest theory as to the building of these monuments, which has of late years been enunciated by Dr. Borchardt, and is now generally accepted. The great Prussian explorer Lepsius, when he examined the pyramids in the ‘forties, came to the conclusion that each king, when he ascended the throne, planned a small pyramid for himself. This was built in a few years’ time, and if his reign were short, or if he were unable to enlarge the pyramid for other reasons, it sufficed for his tomb. If, however, his reign seemed likely to be one of some length, after the first plan was completed he enlarged his pyramid by building another and a larger one around it and over it. Then again, when this addition was finished, and the king still reigned and was in possession of great resources, yet another coating, so to speak, was put on to the pyramid, and so on till colossal structures like the First and Second Pyramid of Giza, which, we know, belonged to kings who were unusually long-lived, were completed. And finally the aged monarch died, and was buried in the huge tomb which his long life and his great power had enabled him to erect. This view appeared eminently reasonable at the time, and it seemed almost as though we ought to be able to tell whether a king had reigned long or not by the size of his pyramid, and even to obtain a rough idea of the length of his reign by counting the successive coats or accretions which it had received, much as we tell the age of a tree by the rings in its bole. A pyramid seemed to have been constructed something after the manner of an onion or a Chinese puzzle-box.

Another interesting point has arisen in connection with the Great Pyramid. Considerable difference of opinion has always existed between Egyptologists and the professors of European archaeology with regard to the antiquity of the knowledge of iron in Egypt. The majority of the Egyptologists have always maintained, on the authority of the inscriptions, that iron was known to the ancient Egyptians from the earliest period. They argued that the word for a certain metal in old Egyptian was the same as the Coptic word for “iron.” They stated that in the most ancient religious texts the Egyptians spoke of the firmament of heaven as made of this metal, and they came to the conclusion that it was because this metal was blue in colour, the hue of iron or steel; and they further pointed out that some of the weapons in the tomb-paintings were painted blue and others red, some being of iron, that is to say, others of copper or bronze. Finally they brought forward as incontrovertible evidence an actual fragment of worked iron, which had been found between two of the inner blocks, down one of the air-shafts, in the Great Pyramid. Here was an actual piece of iron of the time of the IVth Dynasty, about 3500 B.C.

This conclusion was never accepted by the students of the development of the use of metal in prehistoric Europe, when they came to know of it. No doubt their incredulity was partly due to want of appreciation of the Egyptological evidence, partly to disinclination to accept a conclusion which did not at all agree with the knowledge they had derived from their own study of prehistoric Europe. In Southern Europe it was quite certain that iron did not come into use till about 1000 B.C.; in Central Europe, where the discoveries at Hallstatt in the Salzkammergut exhibit the transition from the Age of Bronze to that of Iron, about 800 B.C. The exclusively Iron Age culture of La Tène cannot be dated earlier than the eighth century, if as early as that. How then was it possible that, if iron had been known to the Egyptians as early as 3500 B.C., its knowledge should not have been communicated to the Europeans until over two thousand years later? No; iron could not have been really known to the Egyptians much before 1000 B.C. and the Egyptological evidence was all wrong. This line of argument was taken by the distinguished Swedish archaeologist, Prof. Oscar Montelius, of Upsala, whose previous experience in dealing with the antiquities of Northern Europe, great as it was, was hardly sufficient to enable him to pronounce with authority on a point affecting far-away African Egypt. And when dealing with Greek prehistoric antiquities Prof. Montelius’s views have hardly met with that ready agreement which all acknowledge to be his due when he is giving us the results of his ripe knowledge of Northern antiquities. He has, in fact, forgotten, as most “prehistoric” archaeologists do forget, that the antiquities of Scandinavia, Greece, Egypt, the Semites, the bronze-workers of Benin, the miners of Zimbabwe, and the Ohio mound-builders are not to be treated all together as a whole, and that hard and fast lines of development cannot be laid down for them, based on the experience of Scandinavia.

We may perhaps trace this misleading habit of thought to the influence of the professors of natural science over the students of Stone Age and Bronze Age antiquities. Because nature moves by steady progression and develops on even lines—nihil facit per sal-tum—it seems to have been assumed that the works of man’s hands have developed in the same way, in a regular and even scheme all over the world. On this supposition it would be impossible for the great discovery of the use of iron to have been known in Egypt as early as 3500 B.C. for this knowledge to have remained dormant there for two thousand years, and then to have been suddenly communicated about 1000 B.C. to Greece, spreading with lightning-like rapidity over Europe and displacing the use of bronze everywhere. Yet, as a matter of fact, the work of man does develop in exactly this haphazard way, by fits and starts and sudden leaps of progress after millennia of stagnation. Throwsback to barbarism are just as frequent. The analogy of natural evolution is completely inapplicable and misleading.

Prof. Montelius, however, following the “evolutionary” line of thought, believed that because iron was not known in Europe till about 1000 B.C. it could not have been known in Egypt much earlier; and in an important article which appeared in the Swedish ethnological journal Ymer in 1883, entitled Bronsaldrn i Egypten (“The Bronze Age in Egypt”), he essayed to prove the contrary arguments of the Egyptologists wrong. His main points were that the colour of the weapons in the frescoes was of no importance, as it was purely conventional and arbitrary, and that the evidence of the piece of iron from the Great Pyramid was insufficiently authenticated, and therefore valueless, in the absence of other definite archaeological evidence in the shape of iron of supposed early date. To this article the Swedish Egyptologist, Dr. Piehl, replied in the same periodical, in an article entitled Bronsaldem i Egypten, in which he traversed Prof. Montelius’s conclusions from the Egyptological point of view, and adduced other instances of the use of iron in Egypt, all, it is true, later than the time of the IVth Dynasty. But this protest received little notice, owing to the fact that it remained buried in a Swedish periodical, while Prof. Montelius’s original article was translated into French, and so became well-known.

For the time Prof. Montelius’s conclusions were generally accepted, and when the discoveries of the prehistoric antiquities were made by M. de Morgan, it seemed more probable than ever that Egypt had gone through a regular progressive development from the Age of Stone through those of copper and bronze to that of iron, which was reached about 1100 or 1000 B.C. The evidence of the iron fragment from the Great Pyramid was put on one side, in spite of the circumstantial account of its discovery which had been given by its finders. Even Prof. Pétrie, who in 1881 had accepted the pyramid fragment as undoubtedly contemporary with that building, and had gone so far as to adduce additional evidence for its authenticity, gave way, and accepted Montelius’s view, which held its own until in 1902 it was directly controverted by a discovery of Prof. Pétrie at Abydos. This discovery consisted of an undoubted fragment of iron found in conjunction with bronze tools of VIth Dynasty date; and it settled the matter.* The VIth Dynasty date of this piece of iron, which was more probably worked than not (since it was buried with tools), was held to be undoubted by its discoverer and by everybody else, and, if this were undoubted, the IVth Dynasty date of the Great Pyramid fragment was also fully established. The discoverers of the earlier fragment had no doubt whatever as to its being contemporary with the pyramid, and were supported in this by Prof. Pétrie in 1881. Therefore it is now known to be the fact that iron was used by the Egyptians as early as 3500 B.C.**

* See H. R. Hall’s note on “The Early Use of Iron in Egypt,”

in Man (the organ of the Anthropological Society of

London), iii (1903), No. 86.

** Prof. Montelius objected to these conclusions in a review

of the British Museum “Guide to the Antiquities of the

Bronze Age,” which was published in Man, 1005 (Jan.), No 7.

For an answer to these objections, see Hall, ibid., No. 40.

It would thus appear that though the Egyptians cannot be said to have used

iron generally and so to have entered the “Iron Age” before about 1300

B.C. (reign of Ramses II), yet iron was well known to them and had been

used more than occasionally by them for tools and building purposes as

early as the time of the IVth Dynasty, about 3500 B.C. Certainly dated

examples of its use occur under the IVth, VIth, and XIIIth Dynasties. Why

this knowledge was not communicated to Europe before about 1000 B.C. we

cannot say, nor are Egyptologists called upon to find the reason. So the

Great Pyramid has played an interesting part in the settlement of a very

important question.

It was supposed by Prof. Pétrie that the piece of iron from the Great Pyramid had been part of some arrangement employed for raising the stones into position. Herodotus speaks of the machines, which were used to raise the stones, as made of little pieces of wood. The generally accepted explanation of his meaning used to be that a small crane or similar wooden machine was used for hoisting the stone by means of pulley and rope; but M. Legrain, the director of the works of restoration in the Great Temple of Karnak, has explained it differently. Among the “foundation deposits” of the XVIIIth Dynasty at Dêr el-Bahari and elsewhere, beside the little plaques with the king’s name and the model hoes and vases, was usually found an enigmatic wooden object like a small cradle, with two sides made of semicircular pieces of wood, joined along the curved portion by round wooden bars. M. Legrain has now explained this as a model of the machine used to raise heavy stones from tier to tier of a pyramid or other building, and illustrations of the method of its use may be found in Choisy’s Art de Bâtir chez les anciens Egyptiens. There is little doubt that this primitive machine is that to which Herodotus refers as having been used in the erection of the pyramids.

The later historian, Diodorus, also tells us that great mounds or ramps of earth were used as well, and that the stones were dragged up these to the requisite height. There is no doubt that this statement also is correct. We know that the Egyptians did build in this very way, and the system has been revived by M. Legrain for his work at Karnak, where still exist the remains of the actual mounds and ramps by which the great western pylon was erected in Ptolemaïc times. Work carried on in this way is slow and expensive, but it is eminently suited to the country and understood by the people. If they wish to put a great stone architrave weighing many tons across the top of two columns, they do not hoist it up into position; they rear a great ramp or embankment of earth against the two pillars, half-burying them in the process, then drag the architrave up the ramp by means of ropes and men, and put it into position. Then the ramp is cleared away. This is the ancient system which is now followed at Karnak, and it is the system by which, with the further aid of the wooden machines, the Great Pyramid and its compeers were erected in the days of the IVth Dynasty. Plus cela change, plus c’est la même chose.

The brick pyramids of the XIIth Dynasty were erected in the same way, for the Egyptians had no knowledge of the modern combination of wooden scaffolding and ladders. There was originally a small stone pyramid of the same dynasty at Dashûr, half-way between the two brick ones, but this has now almost disappeared. It belonged to the king Amenemhat II, while the others belonged, the northern to Usertsen (Sen-usret) III, the southern to Amenemhat III. Both these latter monarchs had other tombs elsewhere, Usertsen a great rock-cut gallery and chamber in the cliff at Abydos, Amenemhat a pyramid not very far to the south, at Hawara, close to the Fayyûm. It is uncertain whether the Hawara pyramid or that of Dashûr was the real burial-place of the king, as at neither place is his name found alone. At Hawara it is found in conjunction with that of his daughter, the queen-regnant Se-bekneferurâ (Skemiophris), at Dashûr with that of a king Auabrâ Hor, who was buried in a small tomb near that of the king, and adjoining the tombs of the king’s children. Who King Hor was we do not quite know. His name is not given in the lists, and was unknown until M. de Morgan’s discoveries at Dashûr. It is most probable that he was a prince who was given royal honours during the lifetime of Amenemhat III, whom he predeceased.* In the beautiful wooden statue of him found in his tomb, which is now in the Cairo Museum, he is represented as quite a youth. Amenemhat III was certainly succeeded by Amenemhat IV, and it is impossible to intercalate Hor between them.

* See below, p. 121. Possibly he was a son of Amenemhat III.The identification of the owners of the three western pyramids of Dashûr is due to M. de Morgan and his assistants, Messrs. Legrain and Jéquier, who excavated them from 1894 till 1896. The northern pyramid, that of Usertsen (Senusret) III, is not so well preserved as the southern. It is more worn away, and does not present so imposing an appearance. In both pyramids the outer casing of white stone has entirely disappeared, leaving only the bare black bricks. Each stood in the midst of a great necropolis of dignitaries of the period, as was usually the case. Many of the mastabas were excavated by M. de Morgan. Some are of older periods than the XIIth Dynasty, one belonging to a priest of King Snefru, Aha-f-ka (“Ghost-fighter”), who bore the additional titles of “director of prophets and general of infantry.” There were pluralists even in those days. And the distinction between the privy councillor (Geheimrat) and real privy councillor (Wirk-licher-Greheimrat) was quite familiar; for we find it actually made, many an old Egyptian officially priding himself in his tomb on having been a real privy councillor! The Egyptian bureaucracy was already ancient and had its survivals and its anomalies even as early as the time of the pyramid-builders.

In front of the pyramid of Usertsen (Senusret) III at one time stood the usual funerary temple, but it has been totally destroyed. By the side of the pyramid were buried some of the princesses of the royal family, in a series of tombs opening out of a subterranean gallery, and in this gallery were found the wonderful jewels of the princesses Sit-hathor and Merit, which are among the greatest treasures of the Cairo Museum. Those who have not seen them can obtain a perfect idea of their appearance from the beautiful water-colour paintings of them by M. Legrain, which are published in M. de Morgan’s work on the “Fouilles à Dahchour” (Vienna, 1895). Altogether one hundred and seven objects were recovered, consisting of all kinds of jewelry in gold and coloured stones. Among the most beautiful are the great “pectorals,” or breast-ornaments, in the shape of pylons, with the names of Usertsen II, Usertsen III, and Amenemhat III; the names are surrounded by hawks standing on the sign for gold, gryphons, figures of the king striking down enemies, etc., all in cloisonné work, with beautiful stones such as lapis lazuli, green felspar, and carnelian taking the place of coloured enamels. The massive chains of golden beads and cowries are also very remarkable. These treasures had been buried in boxes in the floor of the subterranean gallery, and had luckily escaped the notice of plunderers, and so by a fortunate chance have survived to tell us what the Egyptian jewellers could do in the days of the XIIth Dynasty. Here also were found two great Nile barges, full-sized boats, with their oars and other gear complete. They also may be seen in the Museum of Cairo. It can only be supposed that they had served as the biers of the royal mummies, and had been brought up in state on sledges. The actual royal chamber was not found, although a subterranean gallery was driven beneath the centre of the pyramid.

The southern brick pyramid was constructed in the same way as the northern one. At the side of it were also found the tombs of members of the royal house, including that of the king Hor, already mentioned, with its interesting contents. The remains of the mummy of this ephemeral monarch, known only from his tomb, were also found. The entrails of the king were placed in the usual “canopic jars,” which were sealed with the seal of Amenemhat III; it is thus that we know that Hor died before him. In many of the inscriptions of this king, on his coffin and stelo, a peculiarly affected manner of writing the hieroglyphs is found,—the birds are without their legs, the snake has no tail, the bee no head. Birds are found without their legs in other inscriptions of this period; it was a temporary fashion and soon discarded.

In the tomb of a princess named Nubhetep, near at hand, were found more jewels of the same style as those of Sit-hathor and Merit. The pyramid itself contained the usual passages and chambers, which were reached with much difficulty and considerable tunnelling by M. de Morgan. In fact, the search for the royal death-chambers lasted from December 5, 1894, till March 17, 1895, when the excavators’ gallery finally struck one of the ancient passages, which were found to be unusually extensive, contrasting in this respect with the northern pyramid. The royal tomb-chamber had, of course, been emptied of what it contained. It must be remembered that, in any case, it is probable that the king was not actually buried here, but in the pyramid of Hawara.

The pyramid of Amenemhat II, which lies between the two brick pyramids, was built entirely of stone. Nothing of it remains above ground, but the investigation of the subterranean portions showed that it was remarkable for the massiveness of its stones and the care with which the masonry was executed. The same characteristics are found in the dependent tombs of the princesses Ha and Khnumet, in which more jewelry was found. This splendid stonework is characteristic of the Middle Kingdom; we find it also in the temple of Mentuhetep III at Thebes.

Some distance south of Dashûr is Mêdûm, where the pyramid of Sneferu reigns in solitude, and beyond this again is Lisht, where in the years 1894-6 MM. Gautier and Jéquier excavated the pyramid of Usertsen (Sen-usret) I. The most remarkable find was a cache of the seated statues of the king in white limestone, in absolutely perfect condition. They were found lying on their sides, just as they had been hidden. Six figures of the king in the form of Osiris, with the face painted red, were also found. Such figures seem to have been regularly set up in front of a royal sepulchre; several were found in front of the funerary temple of Mentu-hetep III, Thebes, which we shall describe later. A fine altar of gray granite, with representations in relief of the nomes bringing offerings, was also recovered. The pyramid of Lisht itself is not built of bricks, like those of Dashûr, but of stone. It was not, however, erected in so solid a fashion as those of earlier days at Gîza or Abusîr, and nothing is left of it now but a heap of débris. The XIIth Dynasty architects built walls of magnificent masonry, as we have seen, and there is no doubt that the stone casing of their pyramids was originally very fine, but the interior is of brick or rubble; the wonderful system of building employed by kings of the IVth Dynasty at Giza was not practised.

South of Lisht is Illahun, and at the entrance to the province of the Fayyûm, and west of this, nearer the Fayyûm, is Hawara, where Prof. Petrie excavated the pyramids of Usertsen (Senusret) II and Amenem-hat III. His discoveries have already been described by Prof. Maspero in his history, so that it will suffice here merely to compare them with the results of M. de Morgan’s later work at Dashûr and that of MM. Gautier and Jéquier at Lisht, to note recent conclusions in connection with them, and to describe the newest discoveries in the same region.

Both pyramids are of brick, lined with stone, like those of Dashûr, with some differences of internal construction, since stone walls exist in the interior. The central chambers and passages leading to them were discovered; and in both cases the passages are peculiarly complex, with dumb chambers, great stone portcullises, etc., in order to mislead and block the way to possible plunderers. The extraordinary sepulchral chamber of the Hawara pyramid, which, though it is over twenty-two feet long by ten feet wide over all, is hewn out of one solid block of hard yellow quartzite, gives some idea of the remarkable facility of dealing with huge stones and the love of utilizing them which is especially characteristic of the XIIth Dynasty. The pyramid of Hawara was provided with a funerary temple the like of which had never been known in Egypt before and was never known afterwards. It was a huge building far larger than the pyramid itself, and built of fine limestone and crystalline white quartzite, in a style eminently characteristic of the XIIth Dynasty. In actual superficies this temple covered an extent of ground within which the temples of Karnak, Luxor, and the Ramesseum, at Thebes, could have stood, but has now almost entirely disappeared, having been used as a quarry for two thousand years. In Roman times this destroying process had already begun, but even then the building was still magnificent, and had been noted with wonder by all the Greek visitors to Egypt from the time of Herodotus downwards. Even before his day it had received the name of the “Labyrinth,” on account of its supposed resemblance to the original labyrinth in Crete.

That the Hawara temple was the Egyptian labyrinth was pointed out by Lepsius in the ‘forties of the last century. Within the last two or three years attention has again been drawn to it by Mr. Arthur Evans’s discovery of the Cretan labyrinth itself in the shape of the Minoan or early Mycenæan palace of Knossos, near Candia in Crete. It is impossible to enter here into all the arguments by which it has been proved that the Knossian palace is the veritable labyrinth of the Minotaur legend, nor would it be strictly germane to our subject were we to do so; but it may suffice to say here that the word

It used to be supposed that the Cretan labyrinth had taken its name from the Egyptian one, and the, word itself was supposed to be of Egyptian origin. An Egyptian etymology was found for it as “Ro-pi-ro-henet,” “Temple-mouth-canal,” which might be interpreted, with some violence to Egyptian construction, as “The temple at the mouth of the canal,” i.e. the Bahr Yusuf, which enters the Fayyûm at Hawara. But unluckily this word would have been pronounced by the natives of the vicinity as “Elphilahune,” which is not very much like

The contrary is evidently the case. Greek visitors to Egypt found a resemblance between the great Egyptian building, with its numerous halls and corridors, vast in extent, and the Knossian palace. Even if very little of the latter was visible in the classical period, as seems possible, yet the site seems always to have been kept holy and free from later building till Roman times, and we know that the tradition of the mazy halls and corridors of the labyrinth was always clear, and was evidently based on a vivid reminiscence. Actually, one of the most prominent characteristics of the Knossian palace is its mazy and labyrinthine system of passages and chambers. The parallel between the two buildings, which originally caused the Greek visitors to give the pyramid-temple of Hawara the name of “labyrinth,” has been traced still further. The white limestone walls and the shining portals of “Parian marble,” described by Strabo as characteristic of the Egyptian labyrinth, have been compared with the shining white selenite or gypsum used at Knossos, and certain general resemblances between the Greek architecture of the Minoan age and the almost contemporary Egyptian architecture of the XIIth Dynasty have been pointed out.* Such resemblances may go to swell the amount of evidence already known, which tells us that there was a close connection between Egyptian and Minoan art and civilization, established at least as early as 2500 B.C.

* See H. R. Hall, Journal of Hellenic Studies, 1905 (Pt.

ii). The Temple of the Sphinx at Gîza may also be compared

with those of Hawara and Knossos. It seems most probable

that the Temple of the Sphinx is a XIIth Dynasty building.

For it must be remembered that within the last few years we have learned

from the excavations in Crete a new chapter of ancient history, which, it

might almost seem, shows us Greece and Egypt in regular communication from

nearly the beginnings of Egyptian history. As the excavations which have

told us this were carried on in Crete, not in Egypt, to describe them does

not lie within the scope of this book, though a short sketch of their

results, so far as they affect Egyptian history in later days, is given in

Chapter VII. Here it may suffice to say that, as far as the early period

is concerned, Egypt and Crete were certainly in communication in the time

of the XIIth Dynasty, and quite possibly in that of the VIth or still

earlier. We have IIId Dynasty Egyptian vases from Knossos, which were

certainly not imported in later days, for no ancient nation had

antiquarian tastes till the time of the Saïtes in Egypt and of the Romans

still later. In fact, this communication seems to go so far back in time

that we are gradually being led to perceive the possibility that the

Minoan culture of Greece was in its origin an offshoot from that of

primeval Egypt, probably in early Neolithic times. That is to say, the

Neolithic Greeks and Neolithic Egyptians were both members of the same

“Mediterranean” stock, which quite possibly may have had its origin in

Africa, and a portion of which may have crossed the sea to Europe in very

early times, taking with it the seeds of culture which in Egypt developed

in the Egyptian way, in Greece in the Greek way. Actual communication and

connection may not have been maintained at first, and probably they were

not. Prof. Petrie thinks otherwise, and would see in the boats painted on

the predynastic Egyptian vases (see Chapter I) the identical galleys by

which, in late Neolithic times, commerce between Crete and Egypt was

carried on across the Mediterranean. It is certain, however, that these

boats are ordinary little river craft, the usual Nile felûkas and

gyassas of the time; they are depicted together with emblems of the

desert and cultivated land,-ostriches, antelopes, hills, and

palm-trees,-and the thoroughly inland and Upper Egyptian character of the

whole design springs to the eye. There can be no doubt whatever that the

predynastic boats were not seagoing galleys.

It was probably not till the time of the pyramid-builders that connection between the Greek Mediterraneans and the Nilotes was re-established. Thence-forward it increased, and in the time of the XIIth Dynasty, when the labyrinth of Amenemhat III was built, there seems to have been some kind of more or less regular communication between the two countries.